Feliks Kazimierz Potocki (1630-1702) built the palace (originally a castle) in 1756. The palace was a residence of many influential nobles and magnates. Today it is functioning as the Chervonohrad branch of the Lviv Museum of the History of Religion with one regular and four temporary exhibitions.

Krystynopil Palace is less known than the younger Potocki domain in Lviv. Nevertheless, it has a ninteresting history and plenty of mysterious legends, which make it a great place to visit. In the 18th century, the family nest of Feliks Kazimierz Potocki was considered the most magnificent in all of Galicia. Later the palace witnessed the decline of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Potocki dynasty. Frequent changes of owners had significant bad effects on the structural condition of the building.

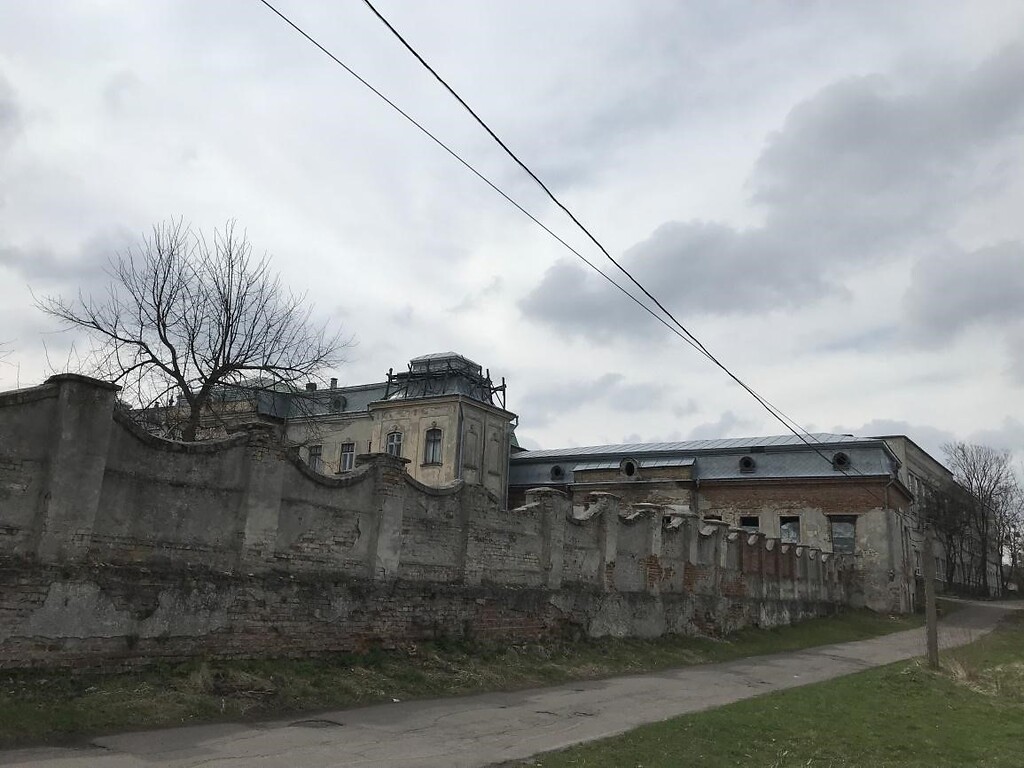

A legend about Stanislaw Potocki, one of the owners of Krystynopil Palace of the 17th century among the big Potocki family is one of the most famous. He was in love with Gertrude Komarovska but their families were against the marriage. Despite the conflict, the couple secretly got married and Gertrude was expecting a baby. By order of Stanislav's father, Gertrude was kidnapped and taken to a monastery in Lviv. Later she mysteriously died. There is a version that on the way to Lviv, Gertrude accidently gasped under blankets where kidnappers hidden her. They were scared and dumped her body in ice-hole in a river (probably the Rata River, tributary of the Bug). After the death of his beloved and child, Stanislav Potocki twice tried to commit suicide but also was married twice more and lived 54 years. From the 18th until the 20th century, the castle owners changed frequently. Additionally, they were unable to maintain the buildings. That caused numerous fires and inappropriate reconstructions. Therefore, most of the building does not exist anymore. The palace needs urgent restoration.

History

The beginning under Feliks Kazimierz Potocki

Krystynopil (modern Chervonograd) is a city in Lviv Oblast, Ukraine which was founded in 1692 by the Polish noble, magnate and Crown Hetman Feliks Kazimierz Potocki (a Hetman is a title for a military leader). The city was named in honor of his wife Krystyna Lubomirska (?-1699). After the foundation of the city, Potocki needed a residence. He had picked the place near the rivers Solokiya and Western Bug and built a fortified castle-type residence. The new Krystynopil residence was strategically important for the Hetman. One of the castle buildings served as the administration of all his residences. Krystynopil was the place of regular location of the part of his army. The founder kept several dozen cannons only in Krystynopil, which were a lot at that time. In addition to artillery, the army consisted of infantry, cavalry and other troops. They lived in the guard house at the entrance to the castle. When Feliks Potocki left or entered the castle, the army honored him with the sounds of horns and tambourines. The estate originally had a wooden fence, which was replaced by a stone wall later. The court of military leaders was as large as the royal one. It had the same government system as other separate principalities of Feliks Potocki. The court consisted of 30 high nobles. Volodymyr Chetvertynsky was the marshal of Potocki's court and Karol Serakovsky was a secretary. Feliks Potocki was living there until his death in 1702.

The 18th century - the golden age of the palace

His descendants also lived in the residence of Krystynopil. Franciszek Salezy Potocki (1700-1772), a grandson of Feliks Potocki, was the next owner of the residence. He had a different view on the estate and decided to reconstruct it with palace features. In 1756, Franciszek hired the famous French architect Pierre Rico de Tirregelli, who created a new project of Potocki Galician residence - luxurious Krystynopil palace in the French style. The construction lasted four years. The palace was built in the style of baroque and early classicism. The royal Palace in Wilanow located near Warsaw was chosen as a sample. A six-hectare park with two courtyards, canals, artificial waterfalls and fountains was laid next to the palace and was similar to Versailles. The entrance to the first courtyard located on the side of town market, the entrance gate had the shape of a triumphal arch and was pushed forward in French style. Next to the first gate, deep in the courtyard, was the entrance to the palace through the second brick gate, which had a clock tower in the middle and houses for the palace garrison on the sides. The second palace courtyard looked like a hexagon and all space was completely filled there. The massive, two-story palace was located on the highest part of the courtyard and its side extensions smoothly passed into the living buildings of the palace.

The palace consisted of a central two-story part and two side parts with mansard roofs. They were covered with wood shingles on the side of the entrance, and the rest with straw. In the past people believed that straws save heat better. In 1904 the central roof was covered with sheet metal and another part remained covered with shingles.

The interior was made in the Rococo style. In addition to 40 rooms, the palace had a ballroom, concert hall, two theaters, a Chinese study and a library. There were separate buildings for the kitchen, administration, brewery, distillery, barracks, stables and utility rooms. The entrance was provided with a guard house and the palace had its own shapel. For visitors, Krystynopil Palace complex had separate living houses for nobles and higher officers meanwhile middle officers had been living with servants.

At various times, the palace was visited by distinguished guests. In 1766 the adventurer Giacomo Casanova visited the Krystynopil Palace and mentioned it later in his infamous memoirs. The palace was also visited by the Austrian Emperor Joseph II. The artists Stanislav Stroinskyi, Franz Smuglevich, Marcello Baccharelli and others worked in the palace. They painted a lot of portraits of the Potocki family, which later were moved to the palace in Tulchin.

The Krysynopil palace had its greatest prosperity in the times of Franciszek Potocki. He could afford such a great repair of grandad house because at that time he was considered the richest person of Rzeczpospolita (the former name of Poland) and had the nickname „Little King of Kyivan Rus”. Franciszek Potocki owned 70 cities, a couple hundred villages but in 1772 Rzeczpospolita suffered the first partition and Krystynopil became part of the Austrian Empire, and it was a double trouble for him. Franciszek Potocki lived in Krystynopil Palace from 1724. In 1772, under threat of execution by the new government, he committed suicide inside the palace. Franciszek Potocki was buried in the Bernardine Church in Krystynopil with his wife Anna.

Steady decline since the end of the 18th century

Afterwards the palace was inherited by his only son, Stanislaw Szczenski Potocki (1751-1805), who was the last Potocki in the history of the Krystynopil Palace. Due to the tragic fate of farther and her beloved Gertrude Komarovska, he decided to move to Tulchyn and built another large palace with a park. He later created a similar park called Sofiyivka, in Uman (which was part of Russia). Stanislaw did it with economic purpose, too. He knew about the conflict with Austian authorities and transferred all his possessions abroad into the Russian Empire.

In the end of the 18th century, Krystynopil went through hard times. In 1781 Stanislaw Potocki sold the city to Prince Adam Poninski (1732/1733-1798) for almost four million Zlotys. Soon the Austrian government confiscated the city from Poninsky for debts and managed them for some time. Then Krystynopil was owned by Kateryna Kossakovska (?-1803), Stanislav Shchensky Potocki's aunt. During these years, the Potocki family nest has significantly weakened. By order of the Austrian authorities, all guns and any means of defense were removed from the palace. Also, the new government has forbidden having an army in the palace. The new government controlled these restrictions strictly. Emperor Joseph II (1741-1790) visited Krystynopil Palace during his visit to Galicia to ensure the safety and loyalty of the Potocki family.

After the death of Kateryna Kossakovska in 1803, the palace was managed by the Austrian government again. In 1818 the city was sold to Maciej Starzeniaski. Over the next hundred years, the owners of the palace were changing five times, and eventually the ownership passed to the Vyshnevsky family. During their reign the palace suffered a fire in 1856, which damaged it significantly. Afterwards, the buildings were partially rebuilt, and a facade was changed. Unfortunately, most of the palace complex was not recovered. New owners did not have the money and the need of such a large and luxurious apartment.

History of the park of Krystynopil Palace

Krystynopil Park had a lot in common with its model, the park of Versailles. It was six hectares of luxurious gardens, mythological sculptures, pavilions and terraces, many fountains, artificial waterfalls and water canals. For the arrangement of water objects, Potocki even changed the waterbed of the river Solokiya. He used the river for the construction of a Dutch sluice system in the park. Water from the river floodplain was supplied to a specially arranged reservoir, and from there to a water pressure machine and sluices. It allowed the water in the park to always remain transparent and clean. The park was surrounded by canals. The central one connected the sluice system with Solokiya, which fed water cascades, fountains and pools. An artificial cascade had two pools with linden trees garden around them. There were fountains on both sides of the upper pool and more pools called ”Neptune’s”, ”Сhestnut” and ”Holland”. Unfortunately, the park wasn’t preserved to this day, now there is a moto track in its place.

The Krystynopil Palace in the 20th and 21st century

A new disaster awaited the palace during the First World War. Russian troops significantly destroyed the palace inside. They broke windows, doors, stairs, damaged fireplaces and more. The palace was the only surviving building among the whole complex. In 1928 the palace was sold to Colonel Sigmond Litynsky. He handed it over to Sokal County for establishing a mining school there in 1935. A lot of changes happened for the last 100 years and today Sokal is a part of Chervonograd region.

The difference between the original and the current appearance of the palace is significant. Some remains of the original complex still could be observed in 1951, when Krystynopil became part of the USSR. During the 1960s great parts of the complex were destroyed. The palace was the only surviving building. Later it was renovated inside and used as a school for some time. After several years a new school was built at the castle's western courtyard.

Today, in the southern part of the former complex exists a moto track called “Girnyk' 'and the sports grounds of the local school. The rest of the territory of the former Krysrynopil park is flooded because it was used as coal mines during Soviet times.

A bed of Anna Elzbieta Potocka and a couple of tapestries are the only preserved interior elements of the former furniture. The tapestries were made between 1755 and 1757 at the Hubert Royal Manufactory in France and now they are displayed at the Pieskowa Skala Historical Museum in Poland.

Future development of the Palace

The palace restoration is discussed for a long time but unfortunately constructions are slowly ruining. Currently the palace is included in the Regional Register of Monuments of National Significance. An example of untimely reaction happened recently. On April 23, 2021, the palace administration held one of the meetings of regional and local government, the museum representatives and volunteers. The topic was the necessity to attract investments for restoration. They discussed a critical condition of the south brick fence. The meeting was over and right the next day the fence collapsed.

Chervonohrad is fitted for a decommunization law initiated in Ukraine in 2015. The local authority and residents of Chervonohrad discussed renaming the city to original Krystynopil but they didn’t realize the project yet because of absence of a united decision.

The museum

Chervonograd Museum of the History of Religion was founded in 1980 in The Basilian Church located around the palace. In 1989 the museum was moved inside the palace. More than 10,000 exhibits of the main and research funds have been collected in the museum over the years of the functioning. The museum has had a restoration workshop since 1992, which helps to conserve and restore the museum's exhibits.

The museum is provided with excursions in five exhibition halls. One of them is used for long-term exhibitions of relevant topics. Other halls are used for temporary exhibits from the funds of other museums, private collections, personal exhibitions of Ukrainian artists and international exhibitions. Chervonograd Museum of the History of Religion has personal temporary exhibits fund, too. The basis of the museum collection are works of Ukrainian sacred art of the17th-19th century. The pride of the collection is unique icons of the 15th and 16th century. There are also many historically valuable household items and clothing (priest clothing of the 17th and 18th century, ritual utensils, embroidered khorugves (a khorugve is a religious banner and a Ukrainian national symbol), tablecloths and towels of the 19th and beginning 20th century, printed documents of the 17th and 18th century represented by fraternal and monastic printing houses of Lviv, Zhovkva, Pochaev, as well as archival documents of the 17th-20th century. Today visitors can view the historical local lore exhibition „Krystynopil in the 17th-19th century”. In other halls art and religion moving exhibitions are located.

The exhibition hall (in the 19th century it was a ballroom) is also used for concerts, lectures, conferences due to its excellent acoustics. The museum often is visited by famous artists and local music groups.

(Maksym Boiko, Lviv Polytechnic National University, 2021)

Internet sources

kray.org.ua: Мандрівки, Палац у Червонограді. Родинне гніздо Потоцьких

krystynopol.info: Палац Потоцьких

krystynopol.info: Червоноградський музей історії релігії